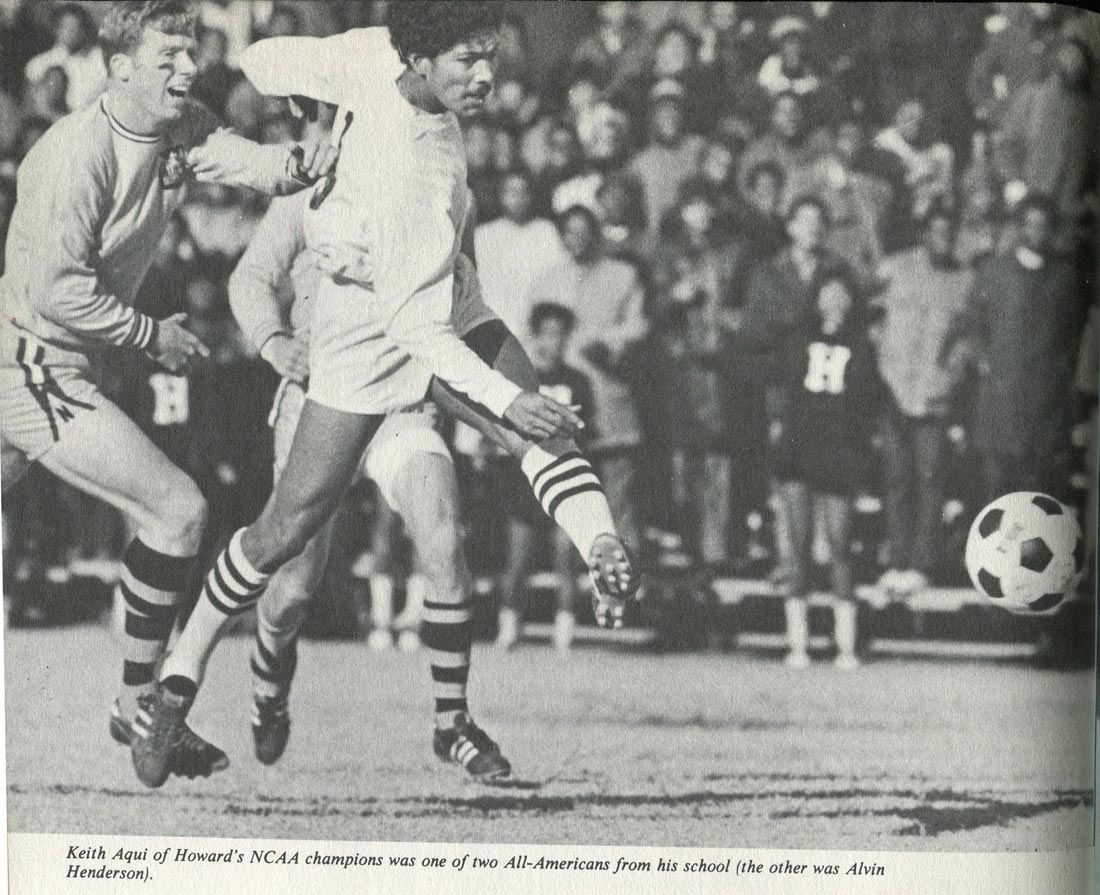

There comes a reminder — a sad reminder, alas — from the 1970s. The death of Keith Aqui brings memories flooding back of college soccer and the exploits of Howard University.

Aqui, who died far too young at 71, was on the Howard team that in 1971 won the NCAA Division I title. A tremendous upset, it may have been the first time an all-black college ever won a Division I NCAA title.

Upset indeed — obviously there were people within college soccer who were greatly upset, who didn’t like what had happened. The NCAA was “notified” that Howard was allegedly using ineligible players. An official NCAA inquiry followed, and Howard was found guilty and stripped of the title.

Aqui was a prime target of the investigators. He was 25, suspiciously old, of course, and the NCAA nailed him and four other players. So Aqui played his last meaningful game for Howard: the bittersweet win-it-lose-it final of 1971.

I was at that final — at the Orange Bowl, on what then-Howard coach Lincoln Phillips called “sandpaper” AstroTurf. I remember Aqui quite well. I never spoke to him, but he spoke to me. He and the whole Howard team spoke to me with their vibrant soccer.

That experience rekindled my interest in the college game, which had been fading rapidly. I had seen far too many games that featured nothing but athleticism. The word I got sick of hearing was “hustle” — that, it seemed, was the be-all and end-all of college soccer back then.

Suddenly here was Howard, sparkling with a different type of soccer, one that seemed to me to be a much truer and livelier version, one that allowed the sport itself to star. I loved it.

Howard had athleticism, of course — you cannot play this sport without plenty of that. But it was athleticism at the service of soccer. It did not dominate the proceedings. The skill of the Howard players did that.

And the player who eventually caught my eye was Aqui, Howard’s goal-scoring forward. He started that 1971 final on the bench with a fever. The fever miraculously vanished when their opponent, Saint Louis University, went up, 2-1. Enter Aqui, who led Howard with 25 goals that season, and enter an ominous threat for Saint Louis. He did not score. But two of his teammates, fellow Trinidadian Alvin Henderson and Mori Diane, did.

Aqui had a special soccer quality that all good forwards need. Difficult to define. I recall a comment from arguably soccer’s greatest player, Diego Maradona, before a game against Germany. “Ganaremos nosotros,” he confidently asserted, “Tenemos mas picardia.” We’ll win, we have more . . . well, more what? More picardia.

And I still can’t quite get the right meaning for picardia. Trickiness? Cheekiness? Sneakiness? Probably craftiness comes closest. Whatever, it’s a knack that Aqui had. The feints, the quick movement, the subtle timing of the moves, the ability to suddenly not be there when the defender moves in, but to be very much there when the ball arrives. A menace, a player who unsettles defenders, who makes them nervous.

There’s a lot to picardia and much of it has a distinct personal quality. No doubt that makes it so difficult to define. I don’t think it can be coached. It wasn’t seen too often in college soccer. It is part of the artistry that soccer needs, but which is too often suppressed in the interests of hustle.

Aqui, whose nickname was “Bronco,” had that artistry. Later I decided that “artful” was the right word for him. His movement could be dangerously direct, or stealthily subtle, whichever he sensed was needed. But it always had the balance and the rhythm of the born soccer player.

These were true soccer values. When they were absent, which they generally were in college soccer, the sport was diminished. Coach Phillips knew their value, and he let Aqui use them. When, so effortlessly, Aqui brought them into action, soccer began to look like “The Beautiful Game.”

That was all I saw of Aqui, in the huge and echoingly empty Orange Bowl. He played in the 1-0 semifinal win over Harvard University, then his substitute role in the final. I would have loved to see more.

A tight-knit bunch, many of his former teammates — many of whom hail from across the African diaspora and the Caribbean — will come together Friday to bid him farewell, at Howard.

Aqui, a senior attorney for the U.S. Department of Treasury who had been “thinking about retirement,” his son Jason said, is survived by his wife Antoinette and three children: Nicole, Ryan, and Jason; and four grandchildren: Tyree, Sydney, Jackson and Caleb.

His college days ended with that 1971 final, but his career is remembered. In 1996, he was elected to Howard’s Hall of Fame.

Howard’s 1971 title was cruelly snatched away from them, but they had their day, as Phillips had his, in 1974 when they again won the NCAA Division I trophy, this time for keeps. The thrills and emotions of that memorable triumph are depicted in the ESPN Films Spike Lee Lil Joint documentary, Redemption Song. And surely Aqui played a big part in the events leading to that belated celebration.