The following is the fourth and final part of Wired868’s look into the short but eventful tenure of the William Wallace-led Trinidad and Tobago Football Association (TTFA); and was done through a series of interviews, on condition of anonymity, with five persons from the United TTFA slate and/or employed elsewhere within the local body:

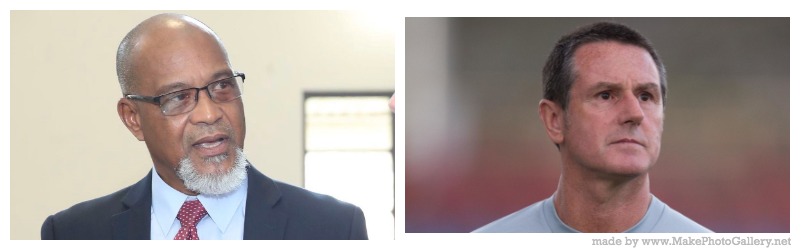

The TTFA technical committee, chaired by Keith Look Loy, had it in their own heads that they had summoned Men’s National Senior Team head coach Terry Fenwick to a meeting—so as to bring him in line with the football body’s other coaches.

Fenwick, who was accompanied by technical director Dion La Foucade, had a different agenda altogether.

The combative Englishman, long thought to be the best coach on the island, had anticipated that the men’s programme would revolve around him. Not only would he head the senior team, but he would guide the youth sides as well.

Arguably, Look Loy’s technical plan initially hinted as much with the Senior National Team assistant coach also serving as Under-20 National Team head coach; and so on, straight down to Under-15 level.

Fenwick interpreted this to mean that the National Senior Team head coach would create the blueprint for the men’s game, which would trickle down to the youth sides. And he would have direct influence on them all. In essence, he would not only be the men’s head coach—but part-technical director too.

Look Loy’s organisational chart did take the overseeing of national youth teams away from the technical director. But, rather than hand it over to Fenwick, those duties went to his technical committee instead.

On top of that, it soon became evident that Fenwick did not even enjoy the same control over the hiring of his assistants as did his predecessors. And, as he tried to put a team together for his maiden international away to Canada, he felt he was not having his way with player selection either.

Look Loy and company were frustrated that Fenwick was more than a month past his deadline to present a technical, tactical and training programme for his team and was the only coach yet to get on to the training ground.

But Fenwick had his own grouses.

“Why you haven’t had your training programmes?!” Fenwick replied. “Because I am busy trying to organise a squad to play Canada for one!

“[…] Instead of trying to get in the way, why don’t you all do what you’re supposed to do and get me the players I want!”

Fenwick was particularly sore that, having wrung verbal commitments out of several talented foreign-born players such as Nick De Leon, Shaq Moore, John Bostock and Ryan Inniss, TTFA director of football Richard Piper said he could not process their paperwork to face Canada, in three months’ time.

“Nick’s sister has already played for Trinidad and yet Piper is saying he can’t process him by June!” said Fenwick. “So why is it taking so long!”

His angst with Piper ran deeper than that. The pair had a strained relationship that dated back to Fenwick’s unsuccessful attempt to buy out the St Ann’s Rangers Pro League club, which Piper managed.

Fenwick pulled out an email from Piper and passed it around to the technical committee members. It was the first official communication between the pair in their current TTFA roles.

The opening read: ‘Good day Terry, it is indeed to me unfortunate that it appears I am being drawn into what appears to be a battle of Testicular Fortitude…’

“Does that sound professional to you?” Fenwick asked the committee.

Look Loy was next on his agenda. Fenwick told his manager, Basil Thompson, to get Moore sorted for his international debut—only to be advised by the technical committee chairman that the player will not come.

The Warriors head coach then got a message from Moore’s agent which complained about being contacted by ‘other’ TTFA representatives.

“I need the administrative side doing their job but I am responsible for my squad and my players!” said Fenwick. “The only person to interact with my players is me!”

Ken Elie, a former soldier and national youth team coach, was aghast.

“What I am hearing here is an employee telling the employer what and how he is going to do his stuff,” said Elie. “No where in the world does that happen! It is the employer who says what he wants done. The employee’s job is only to suggest how he can get it done!”

Fenwick interrupted.

“Fellahs, I am happy to meet this committee anytime,” said Fenwick. “But I am not answerable to you. I am answerable to the board and the president!”

Look Loy was off his feet in a flash and slapped the table so fiercely that La Foucade, who sat between the chairman and the head coach, jumped.

“You will answer to this committee!” said Look Loy, as he jabbed his index finger towards Fenwick. “You and him (pointing to La Foucade) are answerable to me!”

“No, we are not!” Fenwick replied.

La Foucade repeated Fenwick’s refusal but he leaned so far away from Look Loy as he spoke that he was in danger of falling off his chair.

The shouting, from inside the TTFA’s board room, echoed throughout the office.

“You are out of control,” said Fenwick. “Look at your behaviour… I am not accustomed to this attitude at meetings.”

Look Loy was screaming about the efforts he made to give Fenwick his job as head coach. But, unlike La Foucade, the Englishman did not seem intimidated in the slightest. If anything, he needled the technical committee chairman even further.

“You damn well will report to this committee!” said Look Loy.

“Really? Well I will take that up with the president,” Fenwick replied.

In fact, article 10 of Fenwick’s contract said: ‘the coach shall comply with all directives and guidelines issued by the association and as directed by the president…’ And, in the 11 page document, the words ‘technical committee’ were not mentioned together even once.

But then the only TTFA officers who had ever seen Fenwick’s contract at that stage—an agreement that the head coach drew up himself with the help of his lawyer—were president William Wallace and general secretary Ramesh Ramdhan.

“When the chairman is on his feet, you cannot be talking!” Look Loy shouted, slamming the table again. “I am a member of the board; you are an employee of the TTFA…”

“The team doesn’t belong to you!” said Elie. “And you are responsible to the TTFA!”

“He feel nobody in Trinidad knows about football except him!” said Look Loy. “He thinks I will put up with this blasted disrespect!”

And, at that point, Fenwick pushed back his chair and stood up.

“Gentlemen, I have somewhere else to be,” he said.

And he walked right out of the door, as the rest of room looked on with mouths open.

“Where are you going?” asked committee member Dale Tony.

“Let him go!” said Look Loy. “Let him go!”

And as technical committee members discussed a suitable punishment for their maverick head coach, Fenwick posed alongside Wallace and Sports & Games director Omar Hadeed at a photo shoot which sealed a four-year deal with the latter company as the TTFA’s ‘exclusive retail partner’.

“Like [Fenwick] thinks he is a blasted vice-president!” Look Loy subsequently told first vice-president Clynt Taylor, as the remaining United TTFA members demanded that Wallace explain why the Englishman seemed to be marching to the beat of his own drum.

“I will fix it,” said Wallace.

Wallace was trying to keep everyone happy—but the task was getting more implausible every day.

When Peter Miller, a compatriot, friend and business partner of Fenwick’s, first spoke to Wallace during the latter’s campaign for the TTFA presidency, he urged the former Carapichaima East Secondary vice-principal to keep his involvement secret.

“I give you my word,” said Wallace.

Once Miller brought a few lucrative sponsorship deals to the table, Wallace thought, nobody would care about the Englishman’s chequered past as he triumphantly revealed him to the board.

But before the controversial Englishman delivered, he wanted something from the TTFA first.

“So do I stop everything?” asked Miller. “What do I get as my guarantee to move forward?”

Miller wanted TT$4 million over two years, split into monthly payments, with a renewal for another two years on the same terms—once the Englishmen met the parameters he set himself.

This, Miller allegedly said, was non-negotiable. It was supposedly the deal that was arranged with former president Raymond Tim Kee before he pulled out of the election race. And, since Wallace took his place, Miller said he was duty-bound to accept it.

Wallace protested about the payment schedule but the salesman insisted.

“I am not going to change one line of that contract,” he said.

“But I do not have a cent,” said Wallace, “so how am I going to pay you this?”

“Don’t worry,” Miller allegedly replied, “I will take it out of the sponsorship deals that I bring in.”

It sounded like a fair trade off to the TTFA president. But, in the end, the secret contract signed with his ‘marketing director’ stated only that Miller was to be paid US$25,000 (TT$169,000) every month, while there was also a separate payment of US$30,410.95 (TT$205,486) for ‘services provided by Miller on or about 25 November 2019’—which was the day after the TTFA election.

So Miller was due TT$205,486 for promising to bring over TT$50 million in sponsorship to the TTFA; and then another TT$4 million for trying to bring the money he promised to the table.

But, in the end, he could simply trouser all that cash and walk away, without the cash-strapped TTFA ever collecting a cent.

Wallace never took Miller’s contract to an independent attorney, his vice-presidents or the TTFA board before he signed; and he denied the deal existed for close to six months.

Similarly, he took Miller’s advice to sign a four-year deal with Avec Sport without any independent counsel whatsoever.

“[…] Any deal is contingent on us keeping info out of the public forum before anything is agreed upon,” Wallace told his vice-presidents. “We know there are people in the board, like [Brent] Sancho, who are taking copies of everything and leaking it to the media…”

In the end, the TTFA got a four-year deal in which it pays Avec Sport TT$10.2 million for replicas and gift items, so as to get TT$5.2 million worth of kit ‘free’.

“[The Avec Sport deal] is not a sponsorship at all,” said a sport administrator with experience of closing apparel deals with the likes of Adidas and Puma, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “It is a sales contract.”

To date, the Soca Warriors are yet to play in Avec Sport—but the company did send some uniforms for the Women’s National Under-20 Team, as they prepared to jet to the Dominican Republic for Concacaf battle.

The TTFA office staff were so concerned when they received the goods from Avec Sport that they phoned Look Loy. The uniforms were men’s sizes, there were shirts and shorts but not socks, there was no warm-up gear or hotel wear, and the jerseys were white with a sky blue slash.

Ramdhan suggested that the young women play in the Avec Sport gear but use existing Joma kit to train, travel and use at the hotel.

“Ramesh, my country is not playing in white and blue!” said Look Loy. “Which part of my flag is blue?!”

Fifa, by then, were already sniffing around. On 25 February, Fifa finance coordinator Mehmet Dirlik, Concacaf finance manager Alejandro Kesende, Concacaf finance department official Dally Fuentes and Valeria Yepes, an independent auditor, landed in Piarco for a ‘fact finding mission’.

“Perhaps declaring bankruptcy is the only way forward in dealing with this debt,” said Kesende.

“To be honest, I’m not in favour of that,” said Wallace. “And we do have a plan to deal with the debt and I think you will be pleasantly surprised.”

Wallace showed the visitors a memorandum of understanding between the TTFA and Lavender Consultants—an unknown British sports project development company, sourced by Miller, which had no proof of prior work. Lavender promised to give TT$50 million to the local football body to act as middle men in a real estate deal involving the Arima Velodrome.

“The delegation expressed some concerns about the nature of the deal,” TTFA finance committee chairman Kendall Tull later swore in an affidavit.

Fifa chief members association officer Véron Mosengo-Omba later said that the fact-finding team had ‘serious concern over the absence of proper diligence prior to the signing of this agreement with Lavender’.

On 29 February, at the TTFA’s last board meeting under the current administration, the word ‘normalisation’ was raised for the first time at that level. The football body’s bank account had been frozen since 13 February, due to a garnishee order by former technical director Kendall Walkes—a rite of passage that has happened under every football president since Oliver Camps.

“No, no, no; normalisation was never an option,” said Ramdhan. “In fact, Fifa is very pleased with the current administration.”

Tull had precisely targeted the issues within the local football body’s internal set-up and pointed Fifa to his plans to address them.

There was never any doubt that Wallace and his board publicly supported Tull. As such, the board began training sessions on corporate governance, while a human resource audit, payment plans for creditors and budget projections were scheduled.

Wallace inherited a body that operated for decades without any proper corporate structure and safeguards. And Fifa audited the TTFA on an annual basis throughout that period.

If anyone was at fault for the TTFA’s sorry state, how was it Wallace and his team? Was Fifa itself not more culpable?

On the other hand, even as Wallace lauded Tull’s input, the football president was secretly signing million dollar contracts without the approval of the board or anyone else. And, ironically, he was utilising the same internal shortcomings to do so that Tull was trying to close.

Once out of public view, it seemed to be Miller—not Tull—who was setting the TTFA’s corporate agenda.

On 3 March, Ramdhan wrote to a director of D&D Auto World and requested a loan of TT$99,405 to pay the TTFA’s office staff: ‘[…] This represents the net amount payable and will be repaid in US currency based on the exchange rate on the particular day…’

The D&D Auto World director was Ramdhan’s relative.

“[The request for a loan from a relative] betrayed a lack of appreciation of good governance and integrity in financial matters,” said Mosengo-Omba, “and raised serious doubts as to the ability of the TTFA executive to govern, far less to come up with a workable solution and plan for rescuing the association.”

Ironically, Ramdhan only sought out the loan in the first place because Fifa was stalling on making its first payment from the US$1.5 million due to the TTFA in 2020.

But then the TTFA general secretary, remember, promised Mosengo-Omba that as soon as the local body could afford, it would do a forensic audit of the Home of Football and publish its findings—even if it implicated the Fifa official and the world governing body itself.

It was, perhaps, not the greatest incentive for Fifa to wire money to Couva.

On 16 March, the High Court gave Walkes permission to empty the football body’s bank account. The local football had roughly TT$300,000 at First Citizens Bank but owed Walkes roughly TT$5 million—a debt that was due to a flawed contract offered by Tim Kee and an inhumane sacking, against Fifa advice, by Wallace’s predecessor, David John-Williams.

The court action meant another embarrassing headline for the TTFA. But, in reality, things were getting better.

Once Walkes emptied its coffers, control of the TTFA’s bank account returned to Wallace and the local football body was open for business again.

If Fifa sent its first payment now, Walkes could not touch it. He would need to re-open negotiations with Wallace instead; and, failing that, return to the High Court to go through the garnishee process all over again.

Even Look Loy and Fenwick had long made up.

“When big men enter in a meeting with differences and everyone leave smiling,” said Elie, after the technical committee’s combustible first meeting with Fenwick, “somebody’s bullshitting somebody…”

Yet, the second meeting between Fenwick and Look Loy, which was meant to clear the air, lasted barely five minutes.

“So are we okay to work together?” asked a smiling Fenwick.

“Of course!” said Look Loy, with matching enthusiasm.

Neither man looked the other in the eye throughout their ‘make-up’ session.

Maybe Fifa and TTFA would also call ‘truce’. The first Fifa Forward programme tranche was three months late and there was nothing to stop it being paid now. With that money, Wallace could finally start paying his coaches and the new administration would get going in earnest.

On 17 March, Fifa did reach out to Wallace and his team—but it was not the greeting they had anticipated.

‘The Bureau of the FIFA Council has today decided to appoint a normalisation committee for the Trinidad and Tobago Football Association (TTFA) in accordance with article 8 paragraph 2 of the FIFA Statutes.

‘The decision follows the recent FIFA/Concacaf fact-finding mission to Trinidad and Tobago to assess, together with an independent auditor, the financial situation of TTFA. The mission found that extremely low overall financial management methods, combined with a massive debt, have resulted in the TTFA facing a very real risk of insolvency and illiquidity.

‘Such a situation is putting at risk the organisation and development of football in the country and corrective measures need to be applied urgently…’

And to cap the irony, Fifa then appointed the TTFA’s finance manager Tyril Patrick—arguably the most culpable person left at its headquarters where its ‘extremely low overall financial management methods’ was concerned—to run the local body.

At the time, the TTFA board had already taken a decision to suspend Patrick, for an internal investigation, as a direct result of his stewardship under John-Williams.

The TTFA suffered through the bogus ticket fiasco of 1989, the 2006 World Cup bonus dispute and the Mohamed Bin Hammam bribery scandal of 2011 and the free-fall of football standards under John-Williams.

Wallace promised a bright new future.

“The democratically elected TTFA officers reject this Fifa game and reject the concept of Fifa dependency,” said Wallace, as he vowed to legally resist Fifa president Gianni Infantino in the High Court in May. “[…] United TTFA assures the football community and the people of Trinidad and Tobago that we have carefully considered the options, the potential risks and the beneficial outcomes of this struggle to defend the sovereignty of our country and our football.

“[…] We shall prevail.”

By 18 June, the mood around United TTFA had changed considerably, as Wallace’s secret deals tumbled out of the closet.

There was no hint of personal profit for the football president. But it was just as clear that the business he signed off on did not benefit the organisation entrusted to his care.

“I cannot support Wallace any further,” said Look Loy. “I support the vice-presidents. I support the case. We need to remember why Fifa did what they did…”

Will Fifa prevail through legal means or brute force? Would Wallace force the governing body back to the table and negotiate his own survival?

Or will the TTFA’s membership solve the issue itself by changing its leadership, via the local constitution, and having Taylor or the normalisation committee steady the ship until another election can be called?

Eventually, one suspects that the tale of the United TTFA will be written by the winner of this bloody battle.

But, as best as Wired868 could tell, this was their story.