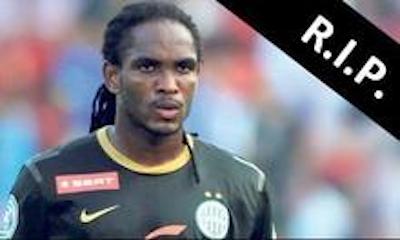

Akeem Adams, a 22-year-old footballer, died on 30 December 2013. Ricardo Moniz, Adams' coach at Ferencvaros, sounds the alarm: he demands a better medical assessment for professional footballers. Furthermore, he warns all trainers, coaches and players worldwide to treat the heart-related medical assessment with utmost seriousness.

Akeem Adams was a talented defender. He made his debut at the age of sixteen in the national team of Trinidad & Tobago. In the summer of 2013, he arrived at Ferencvaros, where he underwent a successful trial period. Coach Moniz was impressed: "He was a beast, a talented player with a strong body." Before Adams signed for Ferencvaros (the winner of the League Cup in 2013), he underwent a medical assessment. No cardiac problems were observed.

On Wednesday 25 September, things went wrong for Akeem Adams. He was in his apartment when he suffered a terrible pain in his chest and arms. When a team mate, who lived in the same complex, rushed to his aid, Adams collapsed. He had apparently had a heart attack. In the hospital his condition deteriorated. He fell into a coma. There were serious complications; the doctors decided to amputate his left leg.

After some five weeks, Adams awoke from his coma, but his condition remained critical. On 30 December, Adams died from a brain haemorrhage.

Ricardo Moniz was closely connected to the welfare of Adams throughout this period. Every day the player received a visit from the coach who, in the 2012-2013 season was proclaimed Trainer of the Year in Hungary, and in the 2011-2012 season, had achieved the Austrian double with Red Bull Salzburg.

Moniz learned that Adams had a rare, genetic disorder that caused plaque (deposit) on his artery. "It had not been detected during the medical assessment."

In Hungary, clubs work with the well-known Lausanne protocol, in order to detect possible cardiac problems. There is considerable criticism of this standard procedure: the protocol is not properly constructed, the predictive value is limited, furthermore, additional investigation is necessary to conclude whether or not a player has a heart condition.

Adams should have been subjected to an additional, extensive heart examination, says Moniz.

"During the medical test they asked him: 'Is there anybody in the family who died as a direct result of a cardio-vascular problem?' Akeem said 'No.' For his father died after a lengthy period of illness as a result of a brain haemorrhage." Because Adams interpreted the question differently, he did not mention his father's brain haemorrhage during the assessment: according to him, his father had not died of heart problems. He said 'No'. Nothing more.

So the doctors did not prescribe any further heart examinations. They were not aware that heart problems are hereditary in Akeem Adams' family. In addition to his father, his grandfather also died at a young age after a brain haemorrhage. And his older brother Akini, it transpired later, also has problems. When Moniz was informed about Akeem's genetic heart condition, he immediately had Akini, who was training temporarily with Ferencvaros, examined extensively. "It turned out that he had an irresponsibly high blood pressure. It was life-threatening."

Moniz refers to the procedure followed during the medical assessment of Akeem Adams: "That question can be interpreted in various ways. That must change. They should ask: 'Are both your parents still alive? No? What was the cause of their death? And what exactly took place?' For only when it emerges that a family member has died of a cardio-vascular condition do they carry out a stress test. If this reveals an anomaly, a CT scan is carried out. That scan immediately shows whether there is plaque. And this can be treated with medication. Then nothing would have happened to Akeem..."

One additional question could have saved Akeem Adams' life.

Scientific research shows that an average of between 0.6 and 3.6 players per 100,000 athletes between the ages of 12 and 35 die from a sudden heart attack. That percentage is higher among footballers.

"If we improve the test, then only one will die," says Moniz, referring to the current protocol. "I want to improve the whole system. It is crazy! They examine a player's knees, his muscles, but the organ that drives it all, the heart, is practically ignored."

The Dutch coach, who previously worked with renowned clubs such as Tottenham Hotspur and Hamburger SV, knows from personal experience that many coaches are unaware of cardio-vascular problems or deficiencies in the current protocol. "Even the director of the course to coach in professional football which I followed did not know about it."

"As coach, I have to protect the players. As trainer, you assume that the players you have available are suitable for top sport. That demands an optimum, thorough medical assessment."

"I want to issue an urgent warning to trainers and players about the seriousness of the medical assessment. It is essential for the health of the players that they answer the questions honestly and comprehensively. They must realise that their life is more important than a football contract. Their coaches must insist that they do this."

"Things went wrong for Akeem. Nobody asked about the cause of his father's death. And that cost Akeem his life."

"The protocol is no good."

FIFPro fully supports Moniz. The worldwide representative of all professional footballers has started a lobby that must result in a better pre-competition medical assessment that is carried out throughout the world.

Moniz: "What happened to Akeem must not be for nothing..."