No Spider-Man on the Web?

The year is 1999, one year after former Strike Squad baby Dwight Yorke makes a £12.6 million move from Aston Villa to Manchester United. The “Red Devils” complete a memorable treble.

The year is now 1989, ten years before Yorke’s Manchester odyssey. The Trinidad and Tobago Senior team is preparing for the Shell Caribbean Cup in Barbados. Current TT Pro League CEO Dexter Skeene is the one who breaks the news to Carter, Leroy Spann and Maurice Alibey that Yorke is hesitating to take up a trial offer with Villa.

Carter has a fit, he tells Wired868, and begins to swear like a sailor.

“When Dwight comes into the room,” he tells Skeene and company, “I’m gonna go mad and then you guys will take over.”

True to his word, he accosts Yorke when he shows up a few minutes later.

“What it is I hearing here?” he asks. “Talk to me. I hear you not going?”

Yorke responds that the manager had told him not to go.

“I started to cuss Dwight Yorke like if obscene was the only language I knew. And then I slammed the door and went outside…”

Not for long. Returning moments later, he takes up where he had left off.

“I don’t care what you or the manager says,” he tells the soon-to-be English Premier League player, “You’re going to leave this national team right now and go on trial in England. You could always play for Trinidad and Tobago, you can’t always play for Aston Villa.

“You feel Aston Villa waiting on you? Anywhere in the world those teams go, they see young players with talent and they give them an invitation. You think they are going to sit around waiting on Dwight Yorke?”

“Boy, you’re calling your agent tonight,” Carter threatens, “and you will report to me.”

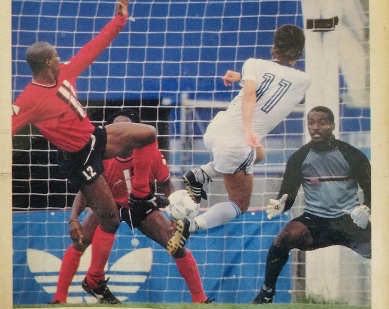

Mere days later, arrangements for the Villa trial were in place and Dwight “The Smiling Assassin” Yorke celebrated with a brace of goals which took Trinidad and Tobago to victory in the final.

“He wrote three books,” Carter told Wired868, “three books and he didn’t mention that! If Dexter Skeene did not bring up that, I would not have known anything. And because of the way I was treated by the Federation in the past, I knew this was a young man I had to take an interest in.

“So Earl Carter and Dexter Skeene played an instrumental part in him accepting that trial.”

Like most of Trinidad and Tobago, Wired868 is well aware that the then not-quite-18-year-old Tobagonian went on to what turned out to be a lengthy and fruitful career in England and in international football, culminating with the captaincy of the 2006 Senior National Team, the first and only one ever to reach the World Cup finals.

However, Wired868 offers no independent verification of the custodian’s story; Wired868 sees it as, even if not accurate in all the details, illustrative of an important characteristic of the brave but brash, 19-year-old goalkeeper from Tacarigua—his determination to be there for his friends and colleagues.

He said it is the reason why, after collecting some 40 caps for his country, he decided to share his knowledge with younger keepers. According to him, he had a hand in the development of former national goalkeepers Leno Fermin, Wayne Lawson and Errol Lovell as well as US goalkeeper and former Fort Lauderdale Strikers player Sam Rosamilia. He says he helped them become the best goalkeepers they could be.

In 1980, it had also led to Carter’s running into trouble with the local federation for taking a stand against the heavy workload the Defence Force players had to endure.

And, he claims, during the ill-fated qualifying campaign for the 1990 World Cup in Italy, he was relegated to the number three keeping spot as a result of a heart-to-heart talk he had with team manager Oliver Camps. Carter had not pulled his punches and had pointed out to the team manager all the areas where he felt coach Everald “Gally” Cummings was going wrong.

He said someone subsequently warned him to be very careful because “Camps and Gally want to fire you.”

And he also claims that, some time after the heart-wrenching loss to the US in November, former national coach Roderick Warner told him that he would not have made the cut for Italy anyway.

“All because I talked,” he told Wired868. “I have always gotten into trouble and I have always talked about the right things for the betterment of the game and the players. People who do that don’t fare well in this society. You’re supposed to take everything and just absorb it and go with the flow.”

So did Carter achieve his mission to be not just the best he could be but the best in the world? It’s accurate to say that for a while he was among the best in the world—if only because he did find himself in the New York Cosmos dressing room, rubbing shoulders with famed players like Brazil’s Pelé and Carlos Alberto and Germany’s Franz Beckenbauer.

If only for that reason, the Spider-Man story would have to be considered a success story. It began in the early 1970’s but not, as was the case with Peter Parker, with a radioactive spider. In 1972, Sir Frank Worrell United coach Vernon Bain convinced the then quarter-miler’s father that his son belonged between the uprights and not on an athletic track. Or in midfield where he had actually turned out on the football field during his schooldays.

Bain told him and his father that he had everything to become the next Lincoln Phillips.

He soon showed that he certainly had the passion and the dedication. “Spider-Man” recalled training relentlessly for six hours per day six days per week, with Sunday being his only rest day. It was a regime that prompted Eddie Hart, one of Carter’s early coaches, to tell Wired868 that the young goalkeeper sometimes struck him as not having all his marbles.

“I have never seen any athlete train as hard or work as hard as Earl ‘Spider-Man’ Carter,” Hart said. “At times I would say, ‘Like this man going off!’”

Alvin Corneal agrees that Carter trained like a beast and notes that his attention to detail was “something else.” He says that the young keeper’s obsession with his craft was such that he would sometimes call him in the early hours of the morning seeking feedback on his performance or advice on how he could improve his weak areas.

Carter himself credits a handful of players in his inner circle with making it easy for him to do what was necessary to improve and maintain his level. He identified Marlon Guerra, Michael Hamlet, Kerry Jamerson, Leroy Spann and Oscar Waldron as being instrumental in ensuring that he consistently raised his level of play and activity and he reserved a special word of praise for Ken Holder.

“I had a network of people from Arima to Port-of-Spain to Couva,” Carter said. “So that is how I was able to maintain my standard. Out of all these players, Ken Holder is the one who was always there for me.

“They were able to lift my standard for me to get on the national team, I need people to know that. It didn’t happen by mistake or it didn’t happen by me training alone. These people helped me maintain my professional lifestyle in an amateur environment.”

The hard work paid off early as Carter had a brief stint as a professional in what was then Surinam with SV Leo Victor in 1976. But after that, things did not always turn out the way the hard-working custodian would have liked. Corneal recalled that, in 1977, he tried to arrange for Carter to go to Stoke to work with the legendary England goalkeeper Gordon Banks. That did not go very well.

“I had worked with Gordon at the English FA, conducting coaching courses,” Corneal said. “But I didn’t get hold of Gordon; he was with the club but he wasn’t on a regular coaching basis with them. [Carter] was with Shrewsbury and it was bad to send him to two clubs. Most times they give you an ultimatum and you have to choose this one or that one.”

The reference to Shrewsbury needs fleshing out.

“We had arranged the trip [to Shrewsbury] for him,” Corneal said, “but I don’t know any of the things that happened there.”

Carter has all the essential details. He—and all of T&T—was under the impression that he was going to Shrewsbury on trial. After all, an Express headline at the time had blared ‘Earl Carter for trial with Shrewsbury.’ But there had been a mix-up.

“When I got there,” Carter explained, “they told me I wasn’t on trial but instead I came there to train. They said Alvin Corneal told them I was the best goalkeeper to pass through Trinidad and Tobago and he wanted to see what help they could offer me.”

There were other ‘misunderstandings.’ In 1980, Carter claimed that a move to Greek club Panathinaikos went awry owing to a contractual arrangement with the national team while a potential transfer to Argentine club Estudiantes came crashing down in 1987 allegedly as a result of “the misplacing of a letter” by a club representative.

Carter’s stay with the Cosmos in 1978-79 was also brief. According to him, he was forced out of the club despite the best efforts of the coach, Eddie Firmani.

“They fired me,” Carter told Wired868, “and coach Firmani told me to keep training. Which coach you know in modern-day football will do something like that? A man is fired and a coach is going out of his way to get a contract for him? No, when you are fired, you are fired.

“One week when [Firmani] wasn’t there, the assistant coach saw me coming into Giants stadium and he asked me what I was doing there. When I told him coach Firmani said I could continue training with the team until something worked out, he said, ‘No, get out of here!’”

And that essentially was that!

Still, Carter was left with fond memories of training alongside Brazilian legend Pelé at Santos. Pelé did not take the playing field during Carter’s stint with the club, but his presence on the training pitch and around the team camp was mesmerising enough to tingle Spidey’s senses.

“The things I saw [Pelé] doing, I said he had to be a magician, words can’t even describe it,” said Carter. “Anybody could dribble but his vision and ability to command the football was really amazing […] He made the game look so simple. It was as though he had eyes behind his head.”

The vision and brilliance of the three-time World Cup winner was unmistakable at Cosmos’ training sessions where he demonstrated a telepathic ability to find his mates wherever they were on the training field.

Carter was often distracted by Pelé’s brilliance when performing his own goalkeeping duties and he reckons that opponents must have felt the same way as well.

“Noel ‘Sammy’ Llewellyn said when he played with Johan Cruyff he would spend more time watching Cruyff’s movement off the ball than paying attention to his own game,” Carter said. “And it was the same with Pelé. He was out of this world!

“The things this man did in training, I said he couldn’t be natural, he couldn’t be human. And he was so humble. He never gave off the impression that he was bigger than anybody.

“I remember when I met him for the first time, he had just come from the Warner Brothers’ office. We bounced up in the elevator and he spoke to me like he had known me his whole life.”

All in all, though, Spider-Man has few regrets. He says he has a lot to be thankful for. He recalls how, in 1982, he was involved in a serious vehicular accident.

“I sustained a serious injury,” Carter explained. “At the end of the surgery, I asked the nurse how bad the injury was and she said ‘I cannot tell you how bad the injury is but from where you came from, you are supposed to give a thanksgiving for being here still.’”

And almost four decades later, he is still here, thankful to be still here and trying to get what is due to him. He does not expect a blockbuster superhero film à la Black Panther or even a more modest one like the other Spider-Man.

But he does wish he could find some film showing him using his “pat down” or his javelin throw; after all, if there is just one creature you’d expect to find somewhere on the World Wide Web, it would be Spider-Man, wouldn’t it?